David Gerrold was Guest of Honor at the 73rd Annual World Science Fiction Convention in Spokane, Washington, the convention itself running between August 19-23, 2015. As you may be aware by now, the Hugo Awards process has been distorted by the emergence of two factions bent on disrupting the normal process of selecting the award winners by way of ballot box stuffing to get their own works nominated, pushing out other legitimate potential entries.

As Guest of Honor, it fell upon Gerrold to set the tone for the rest of the convention with his keynote speech, and we felt that it was so important a message to convey that we asked him permission to reprint that speech here on the pages of the SCIFI.radio web site.

Here is that speech, word for word, as he originally wrote it:

Hello.

My name is David and I am a science fiction fan.

Admitting you have no power over reality is the first step.

I’m here because someone on the committee thinks I know what I’m talking about. I’ll try not to embarrass them.

In 1973, I attended my first Star Trek convention in New York. It was one of the very big fan-run cons, and it was one of the best parties I’d ever been to. The con-committee asked me to be on a panel about writing science fiction. I was happy to say yes.

I arrived at the panel a few minutes early. There was only one track of programming, so there were already several thousand people assembling in the ballroom. I sat down at the table and waited.

A few minutes later, Isaac Asimov came in and sat down beside me. We already knew each other, so I said, “Hi, Isaac,” and he said, “Hi, David.” Then Hal Clement came in and sat down on the other side of me. I admired Hal as much as, if not more, than Isaac. We knew each other a little too. I said, “Hi, Hal,” and he said, “Hi, David.”

And then it hit me. I was sitting between Isaac Asimov and Hal Clement.

And a little voice in my head said, “David, what the hell are you doing, sitting between Isaac Asimov and Hal Clement?” And another little voice in my head — there’s a whole committee in here sometimes – said, “Keep your mouth shut or the audience will be asking the same question.”But as this was a Star Trek convention, and I was the only Star Trek writer in attendance, so the first question came to me. A young fan asked, “How important is scientific accuracy in your scripts.”

I said, “I think scientific accuracy is very very important, so if I don’t know anything, I pick up the phone and call Isaac. And if he doesn’t know, he picks up the phone and calls Hal. So let me just pass the microphone to Hal.” And I did.

The point of the story is that from the very beginning, I have been in a state of awestruck admiration of the science fiction authors who I grew up with, who shaped my childhood and informed my adolescence.

When I was 9 years old, I discovered a book in the Van Nuys Public Library called “Rocket Ship, Galileo.”

“Here, kid. The first one’s free….”

I’m still 9 years old … with 62 years of experience.

Fan is short for fanatic. I am a fan.

I am such a devoted SF fan that when I realized there were books I wanted to read that no one else was writing, I sat down to write them myself.

I am such a devoted fan that I turned down opportunities to have a career in much more profitable fields so I could keep writing science fiction. More than once.

I could have been a lot of other things. I’d rather be a science fiction writer.

Being a science fiction writer — you become a custodian of the future. You get to create possibilities that might someday evolve from probability to inevitability.Being a science fiction writer is the best job in the world. You get to go anywhere in time and space, past or future or sideways into alternate realities and other dimensions. You get to visit all the possibilities and all the impossibilities. A science fiction writer is a literary timelord.

Who wouldn’t want that job?

Now — let me talk about fans. All of us.

This Worldcon — this is the high point of our calendar.

The Worldcon is a self-assembling village, constructed new every year, every time in a different city. And every year, the responsibility for its construction is entrusted to a different committee, a group of people who have willingly, insanely, asked for that privilege.

Year after year, the members of the committee, always volunteers give years of their own time and energy to make this assembly work. So please, before you leave this convention, make sure you thank the committee, the workers, the volunteers, the assistants — everyone who worked so hard behind the scenes so that we, the family of fans could gather and celebrate our love of the sense of wonder.

To be invited as a Guest of Honor at a Worldcon, whether it’s artist, author, fan, or special guest — it is the community’s way of saying, “Attaboy. You done good.”

Speaking as one of this year’s recipients of that acknowledgment — I have to say it is humbling, it is embarrassing, it is overwhelming, and it is also — did I mention overwhelming — it is also overwhelming. Because it is the community saying, “Please stand here, in the same place as Heinlein and Asimov and Clarke and LeGuin and McCaffrey and Herbert and Sheckley and Pohl and Willis and Resnick and all those others who have set the standards of excellence.”

And that’s pretty goddamn overwhelming to the 9-year old boy who discovered a copy of Rocket Ship Galileo in the Van Nuys public library in 1953. I’m still 9 years old, with 62 years of experience.

But as much as being a Guest of Honor is an acknowledgment to be desired by any author or artist or fan, there’s an even greater honor that we rarely talk about, because most of us take it for granted. It’s one that we all share.

It is the honor of being a part of one of the most remarkable communities on the planet.See, I didn’t come here to be honored — well, a little bit — I came here to honor you.

Think about the kind of people we are. We aren’t just dreamers, we’re builders. The stories we’ve written have helped design the future that we’ve built and are continuing to build. Whether it’s things as mundane as sliding doors or smartphones or as mind-blowing as a moon-landing, a space station, and robots exploring Mars and Pluto — none of these things happened by accident. They happened because of the very human urge to explore and discover and ask the next question.

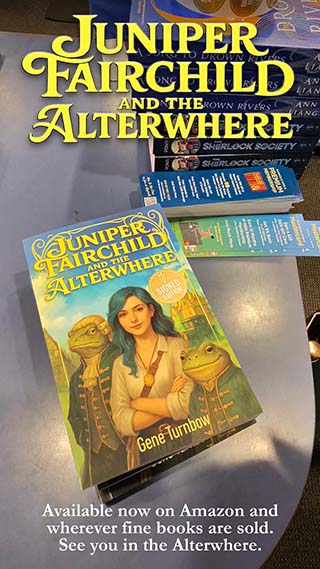

So I’m a fan — part of fandom not because it’s a great place to sell books — [holds up book, this is the commercial] — but because it’s a much better place to confer, converse, and otherwise hobnob with my brother (and sister) wizards. I’m here to enjoy hanging out with old friends and new.

And also because as readers, you are the toughest possible audience. You are the goalposts. You are the challenge that every author must meet. You are the applause or the catcalls. Ultimately, you are the ones who define excellence in this genre. You do it by what you buy and who you honor.

There’s something else about readers. Something amazing. Follow this.

Every time you open a new book, you’re getting inside someone else’s experience. You’re looking out through their eyes, hearing through their ears, feeling what they feel, experiencing a different life.And after you’ve read enough books — I think a couple hundred is the magic number — you become a different person. You become a person who has a sense that the universe is larger than you have ever imagined — and you are not alone in it.

And from that, you start to get the glimmer of understanding that others have thoughts and feelings, wants and needs and desires of their own. And you start to become respectful of that.

We call that empathy.

It is my not very humble opinion that most human problems stem not from a failure to communicate — but from a lack of empathy, a failure to care, a failure of respect.

I think readers — especially the readers who challenge themselves — gain an enhanced sense of empathy. We start to notice and care about people outside our own immediate circle. We start to notice and care about other living things — animals and plants. We start to notice and care about our entire planet. That’s empathy. And from there — we can even start to think about the possibility of life on other worlds, who might live there, how they might be very different than us and who we have to become to meet them.

Empathy is path to true sentience — awareness of others, awareness of the effect we have on them, awareness of the effect we have on our environment, awareness of the future we’re designing for ourselves. From that awareness, we develop wisdom— as individuals, and as a species.

We live in a time when our science is giving us both awareness and ability.

Science fiction allows us to examine the choices before us. That key sentence of wisdom — “If this, then that” — allows us to consider the consequences of our choices and choose wisely. Science fiction encourages the development of transformational thinking.In other words, it makes us weird. The best kind of weird.

We start out looking for grand adventures. We end up finding stories that knock us out of the chair and flat on our ass, gasping for breath.

Sometimes we want to curl up in our comfortable chair and have a nice safe adventure —but sometimes also, we need to be outraged.

Sometimes we need to be kicked out of our comfort zone — the zone of resignation, that place that’s defined by what we’re willing to settle for.

Sometimes outrage is a good thing, because it awakens us to something that’s wrong, something that needs to be challenged, confronted, changed.

And that’s the unspoken goal of this genre — the transformation of the mundane into the marvelous.

As such, science fiction is the most ambitious branch of literature.

Nothing else comes close. No other genre, no other kind of storytelling has such infinite horizons in time and space and possibility. No other kind of storytelling has such an extraordinary impact on its audience. Especially when it takes us to places we’ve never been before, places we’ve never even imagined.For the last half century, I’ve been studying this genre, trying to figure out what makes a great science fiction book or story.

Consider these landmark works: The Stars My Destination, Dune, Ringworld, Aye and Gomorrah, The Left Hand of Darkness, Dhalgren, Slaughterhouse Five, Discworld, When It Changed, The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, Flowers For Algernon, Starship Troopers, “Repent Harlequin!” Said The Ticktock Man, The Ship Who Sang, Rendezvous With Rama, More Than Human, Seven Views of Olduvai Gorge, The Man In the High Castle, and way too many more to list here. And I’m sure you all have your own lists.

For the last half century, I’ve been asking — what makes a great science fiction story? It’s an impossible question. Looking over all these masterworks, there is no single defining criterion for greatness.I think that’s the defining criterion. There isn’t one.

A great science fiction story goes someplace that the genre has never gone before. So you can’t define science fiction by any static criterion — because science fiction, like the culture that nurtures it, is continually evolving.

Earlier this year, I suggested that great fiction is ambitious. More than that, it’s subversive. Because the status quo is the enemy.

But that definition is insufficient. Ambition isn’t achievement. Let me rewrite Sturgeon’s Law. 90% of everything is derivative. 95%. It’s the other 5% that’s innovative.

Derivation is the momentum of the past. There’s nothing wrong with it. I’m not equating derivative with bad or wrong. It is a further and usually necessary exploration of what has previously been established. It’s important.

But the other 5% — well, referring to Sturgeon again, here’s Gerrold’s Corollary. If 95% of everything is crap that’s still no guarantee that the other 5% isn’t.The same is true of innovation. Just because something is innovative doesn’t automatically make it great. Windows 8….

But referring back to that list of great stories above — all of them, every one of them, each in its own way, was innovative. And that is the one thing that all of them do have in common.

Great science fiction is innovative. It defies expectations.

The innovative story breaks rules, demolishes definitions, redefines what’s possible, and reinvents excellence.

The innovative story is unexpected and unpredictable, not only new — but shocking as well. Innovation demands that we rethink what’s possible. Innovation expands the event horizon of the imagination. It transforms our thinking.

And I think that on some level, even though I can’t speak for any other writer but myself, I still think that this is what most of us, maybe even all of us, aspire to — writing that story that startles and amazes and finally goes off like a time-bomb shoved down the reader’s throat. Doing it once establishes that you’re capable of greatness. Doing it consistently explodes the genre.

So yes, that’s the real ambition — to be innovative — to transform thinking — to make a profound difference in who we are and what we’re up to. To be a part of the redesign of who we are and what we’re up to.Because science fiction is the only literature that asks the question, “What does it mean to be a human being?”

Why does existence exist and how does this universe really work? What is our place in it? Who are we? And what do we do in this meager flicker we call life?

I don’t know that the answers are achievable — Godel suggests they aren’t — but when we ask these questions, we stop selling out to the 98% of our DNA that is chimpanzee — we start becoming the missing link between apes and civilized beings.

And…all of this is why I admire science fiction writers so much.

As I see it, the job of the writer is to take the biggest bite of imagination possible — and then grow the jaws to chew it. The challenges are incredible. But when ambition becomes achievement, the world changes. We change.

Because when we stumble or crash or rush headlong, accidentally or on purpose, into the realm of the innovative — at that moment, we’ve not only discovered something new, we’ve also become the kind of person who can discover that thing. Every time out, we get stretched. And there’s no going back to playing small.That’s the real adventure.

I came to science fiction as a nine-year old. I’m still nine years old.

Next year I’ll have 63 years of experience being nine.

Science fiction has been a joyous adventure for every one of those years. And as long as I can keep having joyous adventures — and even a few horrifying ones — I’ll be here.

Thank you. I’ll meet you all in the playground.

We would like to thank Mr. Gerrold for allowing us this reprinting of his words, and we hope that by boosting the signal, we might all enjoy a bit more clarity.

— The Editor

– 30 –

SCIFI.radio is listener supported sci-fi geek culture radio, and operates almost exclusively via the generous contributions of our fans via our Patreon campaign. If you like, you can also use our tip jar and send us a little something to help support the many fine creatives that make this station possible.

Awesome speech . I’ve read The Ship Who Sang and several of McCaffrey ‘s other works